Albania (in Antiquity was called Iliri while in Medievalism Arbëri) as a Mediterranean country with many natural recourses, has been all the time

Naim Frasheri

coveted by the invasions of barbarian invaders. Roman invaders and Turkish invaders in Medievalism prevented too much the development of Albanian art and literature.

The art has had a development with ups and downs and due to its nature, (sculptures, mosaics, wall murals, etc) do exists proves and works since Antiquity. On the contrary, Albanian Literature hasn’t had this fortune. The first documents of its existence are found around the year 1400. The expansion of the Ottoman Empire pushed many Albanians from their homeland during the period of the Western European Renaissance humanism.

Among the Albanian emigrants that became known in the humanist world are historian Marin Barleti (1460-1513) who in 1510 published in Rome the history of Skanderbeg, which was translated almost into all European languages, or Marino Becichemi (1408-1526), Gjon Gazulli (1400-1455), Leonicus Thomeus (1456-1531), Michele Maruli (15th century), Michele Artioti (1480-1556) and many others who were distinguished in various fields of science, art and philosophy. The cultural resistance first of all was expressed through the elaboration of the Albanian language in the area of church sacrifices and publications, mainly of the Catholic confessional region in the North, but also of the Orthodox in the South.

The Protestant reforms invigorated hopes for the development of the local language and literary tradition when the cleric Gjon Buzuku brought into the Albanian language the Catholic liturgy, trying to do for the Albanian language what Luther did for German. The Missal by Gjon Buzuku, published by him in 1555, is considered to date as the first literary work of written Albanian. The refined level of the language and the stabilized orthography must be a result of an earlier tradition of writing Albanian, a tradition that is not known. But there are some fragmented evidences, dating earlier than Buzuku, which indicate that Albanian was written at least since 14th century.

The first known evidence dates from 1332 and deals with the French Dominican Guillelmus Adae, Archbishop of Antivari, who in a report in Latin writes that Albanians use Latin letters in their books although their language is quite different from Latin. Of special importance in supporting this are: a baptizing formula (Unte paghesont premenit Atit et Birit et spertit senit) of 1462, written in Albanian within a text in Latin by the bishop of Durrës, Pal Engjëlli; a glossary with Albanian words of 1497 by Arnhold Von Harff, a German who had travelled through Albania, and a 15th century’s fragment from the Bible by the Gospel of Matthew, also in Albanian, but in Greek letters.

Albanian writings of these centuries must not have been religious texts only, but historical chronicles too. They are mentioned by the humanist Marin Barleti, who, in his book The Siege of Shkodër, (1504), confirms that

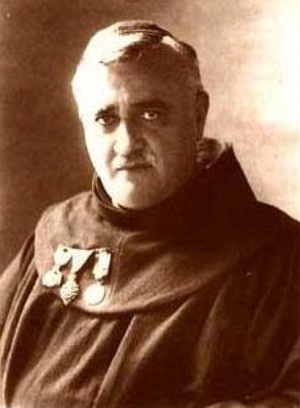

Gjergj Fishta

he went through such chronicles written in the language of the people (in vernacular lingua). Despite the obstacles generated by the Counter-Reformation which was opposed to the development of national languages in Christian liturgy, this process went on uninterrupted. During the 16th to 17th centuries, the catechism Christian Teachings, (1592) by Lekë Matrënga, The Christian Doctrine, (1618, and Roman Ritual, 1621, by Pjetër Budi, the first writer of original Albanian prose and poetry, an apology for Gjergj Kastrioti (1636) by Frang Bardhi, who also published a dictionary and folklore creations, the theological-philosophical treaty Cuneus Prophetarum (The Band of Prophets) (1685) by Pjetër Bogdani, the most universal personality of Albanian Medievalism, were published in Albanian language.

Bogdani’s work is a theological-philosophical treatise that considers with originality, by merging data from various sources, principal issues of theology, a full biblical history and the complicated problems of scholasticism, cosmogony, astronomy, pedagogy, etc. Bogdani brought into Albanian culture the humanist spirit and praised the role of knowledge and culture in the life of man; with his written work in a language of polished style, he marked a turning point in the history of Albanian literature.

Pjetër Bogdani

Another important writer of the Early Albanian Literature was Jul Variboba. During 18th century, the literature of Orthodox and Muslim confessional cultural circles witnessed a greater development. An anonymous writer from Elbasan translated into Albanian a number of sections from the Bible; T. H. Filipi, also from Elbasan, brought the The Old and the New Testament. These efforts multiplied in the following century with the publication in 1827 of the integral text of the The New Testament by G. Gjirokastriti and with the big corpus of (Christian) religious translations by Konstandin Kristoforidhi (1830-1895), in both main dialects of Albanian, publications which helped in the process of integrating the two dialects into a unified literary language and in setting up the basis for the establishment of the National Church of the Albanians with the liturgy in their own language.

Although in opposite direction with this tendency, the culture of Voskopoja is also to be mentioned, a culture that during the 17th century became a great hearth of civilization and a metropolis of the Balkans peninsula, with an Academy and a printing press and with personalities like T. Kavaljoti, Dh. Haxhiu, G. Voskopojari, whose works of knowledge, philology, theology and philosophy assisted objectively in the writing and recognition of Albanian. Although the literature that evolved in Voskopoja was mainly in Greek, the need to erect obstacles to Islamization made necessary the use of national languages, encouraging the development of national cultures. Walachian and Albanian were also used for the teaching of Greek in the schools of Voskopoja, and books in Walachian were also printed in its printing presses. The works of Voskopoja’s writers and savants have brought in some elements of the ideas of the European Enlightenment. The most distinguished of them was Teodor Kavaljoti. According to the notes of H.E. Thunman, the work of Kavaljoti, which remained unpublished, in most part deals with issues from almost all branches of philosophy. It shows the influence of Plato, Descartes, Malebranche and Leibniz.

A result of the influence of Islam and the culture of the invader was the emergence, during 18th century, of a school of poetry, or of a literature

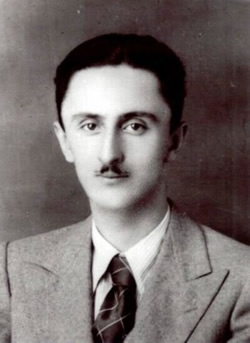

Millosh Gjergj Nikolla – Migjeni

written in Albanian language but by letters of an Arabian alphabet. Its authors such as N. Frakulla, M. Kyçyku, S. Naibi, H.Z. Kamberi, Sh. and D. Frashëri, Sheh Mala, and others dealt in their works with motifs borrowed from Oriental literature, wrote religious texts and poetry in a language suffocated by orientalism and developed religious lyric and epic. The 19th century, the century of national movements in the Balkans, found Albanians without a sufficient tradition of a unitary development of the state, language and culture but, instead, with an individualistic and regionalist mentality inherited from the supremacy of clan and kinship and consequently with an underdeveloped national conscience, though with a spirit of spontaneous rebellion. In this historical cultural situation emerged and fully developed an organized ideological, military and literary movement, called National Renaissance. It was inspired by the ideas of National Romanticism and Enlightenment, which were cultivated among the circles of Albanian intelligentsia, mainly emigrants in the old settlements in Italy and the more recent ones in Istanbul, Bucharest, USA, Sofia and Cairo.

National Renaissance, nurturing the Albanian as a language of culture, the organization of national education and the establishment of a national literature on the cultural level as well as the creation of the independent state – these were the goals of this movement which gave birth to the school of Albanian Romanticism. It was imbued with the spirit of national liberation, with the nostalgia of the emigrants and the rhetorical pathos of past heroic wars. This literary school developed the poetry most. Regarding the motifs and poetical forms, its hero was the ethical man, the fighting Albanian, and to a lesser degree the tragic man. It is closely linked with the folklore tradition.

The pursuit of this tradition and the publications of Rhapsody of an Arbëresh Poem in 1866 by Jeronim De Rada, of Collection of Albanian Folk Songs and Rhapsodies of Albanian Poems, in 1871 by Zef Jubani, Albanian Bee in 1878 by Thimi Mitko, etc., were part of the cultural program of the National Renaissance for establishing a compact ethnic and cultural identity of Albanians.

Two are the greatest representatives of Albanian Romanticism of 19th century: Jeronim De Rada(1814-1903), and Naim Frashëri (1846-1900),

born in Albania, educated at Zosimea of Ioannina, but emigrated and

deceased in Istanbul. The first is the Albanian romantic poet brought up in the climate of European Romanticism, the second is the Albanian romanticist and pantheist who merges in his poetry the influence of Eastern poetry, especially Persian, with the spirit of the poetry of Western Romanticism.

De Rada wrote a cycle of epical-lyrical poems in the style of Albanian rhapsodies: Këngët e Milosaos(The Songs of Milosao), 1836, Serafina Topia 1839, Skënderbeu i pafat (Unlucky Skanderbeg) 1872-1874 etc. with the ambition of creating the national epos for the century of Skanderbeg. Following the traces of Johann Gottfried Herder, De Rada raised the love for folk songs in his poetry and painted it in ethnographic colors. His works reflect both the Albanian life with its characteristic customs and mentalities, and the Albanian drama of the 15th century, when this land’s indomitable folk fell to the Ottoman yoke. The conflict between the happiness of the individual and the tragedy of the nation, the scenes by the riversides, women gathering wheat in the fields, the man going to war and the wife embroidering his belt, all represented with a delicate lyrical feeling.

Naim Frashëri wrote a pastoral poem Shepherds and Farmers (1886), a collection of philosophical, patriotic and love lyrics Summer Flowers, (1890), an epical poem on Skanderbeg The History of Skanderbeg (1898), a religious epical poem Qerbelaja (1898). Naim Frashëri established modern lyrics in Albanian poetry. In the spirit of Bucolics and Georgics of Virgil, in his Shepherds and Farmers he sang to the works of the land tiller and shepherd by writing a hymn to the beauties of his fatherland and expressing the nostalgia of the emigrant poet and the pride of being Albanian. The longing for his birthplace, the mountains and fields of Albania, the graves of his ancestors, the memories of his childhood, feed his inspiration with lyrical strength and impulse.

The inner experiences of the individual freed from the chains of medieval, Oriental mentality on one hand and the philosophical pantheism imbued with the poetical pantheism of the European Romanticism on the other hand, give to the lyrical meditations of Frashëri a universal human and philosophical dimension. The most beautiful poems of Summer Flowers collection are the philosophical lyrics on life and death, on time that goes by and never comes back leaving behind tormenting memories in the heart of man, on the Creator melt with the Universe. Naim Frashëri is the founder of the national literature of the Albanians and of the national literary language. He raised Albanian to a modern language of culture, evolving it in the model of the popular speech.

The world of the romantic hero with its vehement feelings is brought to Albanian Romanticism by the poetry of Zef Serembe. The poetry of Ndre Mjeda and Andon Zako Çajupi, who lived at the end of Renaissance, bears the signs of disintegration of the artistic system of Romanticism in Albanian literature.

Çajupi (1866-1930) is a rustic poet, the type of a folk bard, called the Mistral of Albania; he brought to Albanian literature the comedy of customs and the tragedy of historical themes. Graduated by a French college in Alexandria and the Geneva University, a good connoisseur of French literature, Çajupi was among the first to bring into Albanian language La Fontaine’s fables, thus opening the way to the translation and adoption of works of world literature into Albanian, which have been and remain one of the major ways of communication with the world culture.

Distinguished writers of this period are: Naum Veqilharxhi, Sami Frashëri, Pashko Vasa, Jeronim de Rada, Gavril Dara the Younger, Zef Serembe, Naim Frashëri, Dora d’Istria, Andon Zako Çajupi, Ndre Mjeda, Luigj Gurakuqi, Filip Shiroka, Mihal Grameno, Risto Siliqi,Aleksander Stavre Drenova, etc.

The main direction taken by the Albanian literature between the two World Wars was realism, but it also bore remnants of romanticism.

Gjergj Fishta (1871-1940), wrote a poem of national epos breadth The Highland Lute in 17.000 verses, in the spirit of Albanian historical and legendary epos, depicting the struggles of Northern highlanders against Slav onslaughts. With this work he remains the greatest epical poet of Albanians. A Franciscan priest, erudite and a member of the Italian Academy, Gjergj Fishta is a multifaceted personality of Albanian culture: epical and lyrical poet, publicist and satirist, dramatist and translator, active participant in the Albanian cultural and political life between the two Wars. His major work, The Lute of the Highlands, is a reflection of the Albanian life and mentality, a poetical mosaic of historic and legendary exploits, traditions and customs of the highlands, a live fresco of the history of an old population, which places on its center the type of Albanian carved in the Calvary of his life along the stream of centuries which had been savage to him.

Fishta’s poem is distinguished by its vast linguistic wealth, is a receptacle for the richness of the popular speech of the highlands, the live and infinite phraseology and the diversity of clear syntax constructions, which give vitality and strength to the poetic expression. The poetical collections The Fairies’ Mead with patriotic verse and Paris’s Dance) with verses of a religious spirit, represent Fishta as a refined lyrical poet, while his other works Parnassus’ Anises and Babatas’ Donkey represent him as an unrepeatable satirical poet.

The typical representative of realism was Millosh Gjergj Nikolla, Migjeni (1913-1938). His poetry Free Verses, 1936, and prose are permeated by a severe social realism on the misery and tragic position of the individual in the society of the time. The characters of his works are people from the lowest strata of Albanian society. Some of Migjeni’s stories are novels in miniature; their themes represent the conflict of the individual with institutions and the patriarchal and conservative morality. The rebellious nature of Migjeni’s talent broke the traditionalism of Albanian poetry and prose by bringing a new style and forms in poetry and narrative. He is one of the greatest reformers of Albanian literature, the first great modern Albanian writer.

Lasgush Poradeci (1899-1987), a poetical talent of a different nature, a brilliant lyrical poet, wrote soft and warm poetry, but with a deep thinking and a charming musicality The Dance of Stars, 1933, The Star of Heart, 1937.

Fan Stilian Noli (1882-1965) is one of the most versatile figures – he was a

Fan S. Noli

distinguished poet, historian, dramatist, aesthete andmusicologist, publicist, translator and master of the Albanian language. He wrote the plays The Awakening and Israelites and Philistines; he published articles and translated in Greek Sami Frashëri’s work Albania -her Past, Present and Future. In 1947 he published in English the study Beethoven and the French Revolution.

He translated into Albanian many liturgical books and works of major writers such as Omar Khayyam, William Shakespeare, Henrik Ibsen, Miguel de Cervantes and others. With his poetry, non-fiction, scientific and religious prose, as well as with his translations, Noli has played a fundamental role in the development of the modern Albanian. His introductions to his own translations of world literature made him Albania’s foremost literary critic of the inter-war period. Fan Noli also led the democratic revolution that ousted King Zog’s regime during the middle 1920’s, though his peaceful governing was short-lived.

Albanian literature between the two Wars did not lack manifestations of sentimentalism Foqion Postoli, Mihal Grameno and of belated classicism, especially in drama Et’hem Haxhiademi. Manifestations of the modern trends, impressionism, Symbolism, etc. were isolated phenomena in the works of some writers Migjeni, Poradeci, and Asdreni, that did not succeed in forming a school. Deep changes were seen in the system of genres; prose Migjeni, F. S. Noli, Faik Konica, Ernest Koliqi, Mitrush Kuteli, etc.; drama and satire Gjergj Fishta, Kristo Floqi, developed parallel to poetry. Ernest Koliqi wrote subtle prose, full of coloring from his town of Shkodër, Trader of Flags, 1935. Mitrush Kuteli is a magician of the Albanian language, the writer that cultivated the folk style of narration into a charming prose, Albanian Nights, 1938; Ago Jakupi, 1943; Kapllan Aga of Shaban Shpata, 1944.

Faik Konica is the master who gave Albanian prose a modern image. He was born in Konitsa, a small town in Epirus, which following the decisions of the London Conference of 1913 that shrank the Albanian state to the present borders, remained with Greece. Coming from a renowned family, inheriting the title of Bey and the conscience of belonging to elite, which he manifested strongly in his life and work, he discarded Oriental mentality, inherited from the Ottoman occupation, with a joking smile that he translated into a cutting sarcasm in his work. He attended for one year the Jesuit College of Shkodër, then the Imperial Lyceum in Istanbul, studied literature and philosophy at Dijon University, France, and completed his higher studies at Harvard University, where, in 1912, got a Master’s degree (Master of Arts).

Erudite, knowledgeable in all major European languages and some Eastern ones, a friend of Guillaume Apollinaire, called by foreigners “a walking encyclopedia”, Konica became the model of Western intellectual for the Albanian culture. Since his youth he was dedicated to the national movement, but contrary to the mythical, idealizing and romanticizing feeling of the Renaissance, he brought in it the spirit of criticism and experienced the perennial pain of the idealist who suffers for his own thoughts. He established the Albania magazine (Brussels 1897-1900,London 1902-1909), that became the most important Albanian press organ of the Renaissance. Publicist, essayist, poet, prose writer,translator and literary critic, he, among others, is the author of the studies L’Albanie et les Turcs (Paris 1895), Memoire sur le mouvement national Albanais (Brussels, 1899), of novels “An Embassy of the Zulu in Paris”,1922, and Doctor Needle, 1924, as well as of the historical-cultural work Albania – the Rock Garden of South – Eastern Europe published posthumously in Massachusetts in 1957.

The literature of the Albanians of Italy in the period between the two Wars continued the tradition of the romanticist school of the 19th century. Zef Skiro (1865-1927) through his work Return, 1913, In Foreign Soil, 1940, wanted to recover the historical memory of Albanians emigrated since the 15th century after the death of Skanderbeg.

Distinguished writers of this period are: Fan Stilian Noli, Gjergj Fishta, Faik Konica, Haki Stërmilli, Lasgush Poradeci, Mitrush Kuteli, Migjeni (Millosh Gjergj Nikolla), etc. Also another distinguished writer of Albanian Romanticism who was published in Albania and abroad was, Lazar Eftimiadhi. A graduate of Sorbone, he wrote several articles introducing the Albanian reader to major works of western literature. He also translated works of writers like Hans Christian Andersen, and collaborated with At Gjergj Fishta and others in many important translations. After World War II, Albanian literature witnessed a massive development.

The main feature of literature and arts of this period was their ideologically oriented development and the elaboration of all genres, especially of novel, which despite of the lack of any tradition came to the lead of the literary process. The most elaborate type of novel was the novel of socialist realism of ethical and historical character, with a linear subject matter (Jakov Xoxa, Sterjo Spasse), but novels with a rugged composition, open poetics and a philosophical substratum issuing from association of ideas and historical analogies (Ismail Kadare, Petro Marko) as well as the satirical novel are not lacking (Dritëro Agolli).

The literature of this period developed within the framework of socialist realism, the only direction allowed by official policy. But beyond this framework, powerful talents created works with an implicit feeling of opposition and with universal significance.

The dissident trend in literature was expressed in different forms in the works of Kasëm Trebeshina, Bilal Xhaferri, Minush Jero, Koço Kosta, etj, who either tried to break out the canons of the socialist realism method or introduced heretic ideas for the communist totalitarian ideology.

Albania’s best-known contemporary writer is Ismail Kadare, born in 1935 whose 15 novels have been translated into 40 languages. With the poem What Are These Mountains Musing On, 1964; Sunny Motifs, 1968; Time, 1976; and especially with his prose The General of The Dead Army, 1963; The Castle, 1970; Chronicle in Stone), 1971; The Great Winter, 1977; The Three-Arched Bridge, 1978; The Pyramid, 1992; Spiritus 1996; etc. The work of Kadare represents an artistic encyclopedia of Albanian life. The philosophy, beliefs, dramas and historical and cultural traditions of Albania, filtered through the artistry of the writer, in Kadare’s work express the vitality of the spiritual culture of the Albanian people. Kadare creates a modern prose making wide use of historical analogies, parables and associations, Albanian legends and mythology. Starting from the epic world of medieval legends and ballads, the prose of Kadare brings ancient folk traditions ‘up to date’ by showing their relevance to the modern world.

After 1990, in post-communism period, Albanian creators, writers and artists, members of the Albanian League of Writers and Artists, believed more in their liberation and the liberation of artistic creativity in general. It was worked a lot in a hurry to catch the lost time. There was a huge boom of creativity. Many of the prohibited creations were reassessed and were published. Persecuted figures of the past like Faik Konica, Gjergj Fishta, Ernest Koliqi, etc, dissidents of the communist era like Bilal Xhaferri, Kasem Trebeshina, Pjetër Arbnori etc were revalued. Thus, ALWA contributed to the appreciation of art, literature and authors prohibited.

However during the post-communist period, with a democracy more problematic and highly politicized, the League of Writers and Artists is imposed an adulatory attitude toward the ruling party, the right or the left. Again the government has tried to usurp this institution and has appointed leaders of Albania artists taking advantage of the economic difficulties that writers, artists and organizations experienced. Finally, after ALWA managed to escape from politics, was found without economic support and on the verge of bankruptcy. In this difficult situation the state turned its back, got the building where its headquarters was but writers and artists did not abandon it. Writers and artists are those who keep alive ALWA in this difficult period full of crisis.

Albanian writers continue to create decent work, although without the economic benefits.

Prose writer like Ismail Kadare, Fatos Kongoli, Hysen Sinani, Shefki Hysa and poets like Visar Zhiti, Sazan Goliku, Namik Mane, etc. have written and published many works that address social problems of the time.